The Service Corps and Departments

1881 to 1902

At the culmination of the 1881 Cardwell and Childers Reforms, Great Britain was deeply divided into strata’s based on social class and associated perceptions of breeding and wealth. In general the landed gentry and the upper echelons of the middle class populated the cavalry and infantry with its officers, and the better educated provided a regiment of artillery and a corps of engineer staff. However, the services and departments that were necessary to support the fighting part of the army in the field were often divided into two.

In part this was because before 1855 some elements had been organised by the Board of Ordnance, such as artillery and engineers and transport and storage, and some by the Treasury, such as the commissary services that kept a control on supply, and expenditure. While the artillery and engineers had now joined the cavalry and infantry under a single headquarters, and the latter had merged the hitherto separate engineer staff with the men of the sappers and miners, there was still a tendency to keep the ostensibly non-combatant support elements separate from the combatant arms.

Another factor was formal qualification, with those holding professional credentials often placed in a separate department from the more menial functionaries who were also crucial to the creation of a coherent set of services, as had previously been the case with the engineers, and sappers and miners. In the case of supply and transport this led to officers being placed in a 'Commissariat and Transport Staff' and their men organised in a 'Commissariat and Transport Corps'. Even the rank titles of the Commissariat officers were entirely different to those of the rest of the army, as if to underline their non-combatant status. In a similar manner stores facilities were organised by officers within an 'Ordnance Department' while the men required did the hands-on work within an 'Ordnance Store Corps'. In a likewise manner the officers dealing with pay were organised in an Army Pay Department, whilst their clerical support was provided by the Corps of Military Staff Clerks , along with regimental clerks where appropriate. In the same pattern, surgeons below general rank equivalent and less those surgeons of the Horse and Foot Guards, were organised in an Army Medical Department, whereas the men needed to work under their instruction were a part of the Army Hospital Corps. The army was essentially a Christian one and spiritual needs were attended to by clerics of the Army Chaplains Department, who again had discrete titles to mark their status. In an almost mirror image of the medical services, veterinary surgeons and assistants were brought within an Army Veterinary Department, with the same exceptions relating to general officer equivalents, and those serving in the Horse Guard regiments, who remained separate.

As well as these larger services, there were smaller organisations that might be described as miscellaneous staff functions ranging from Provost, through Prison Governors, to Inspectors of Schools, Barracks Masters, Garrison Staff, Royal Hospitals, and the Unattached List, each of which contained officers wearing uniform and insignia.

This then was the background to a divided army that mirrored the social peccadillo’s and professional snobberies of their age, and the next section of this series focuses primarily on the foregoing organisations officer insignia at the time of the 1883 Dress Regulations. However, it was a period of great change and, as with the previous sections, alterations in pattern will be shown reflecting the further reorganisation of support services and departments up to the close of Queen Victoria's reign in 1902.

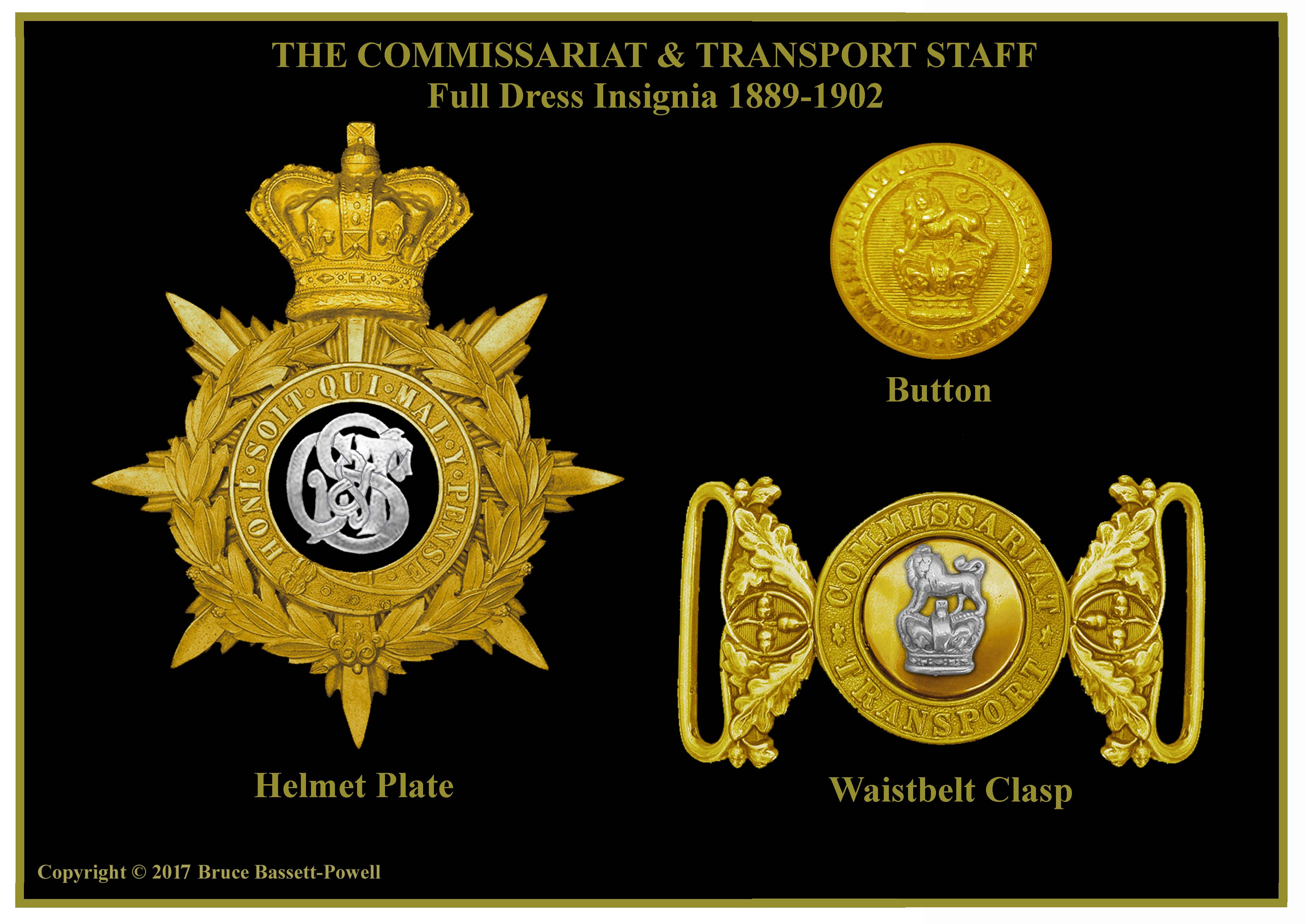

The Commissariat and Transport Staff

1881 to 1888

Before 1869, supply duties had been the responsibility of the Commissariat, a uniformed civilian body. In 1869, the civilian commissaries of the Commissariat and the military officers of the Military Train amalgamated into the Control Department. The following year the other ranks of the Military Train were re-designated as an Army Service Corps (ASC), destined to be the first, but not last use of this title, and officered by the Control Department. In November 1875, the Control Department was divided into the Commissariat and Transport Department and the Ordnance Store Department. In January 1880, the Commissariat and Transport Department was renamed the Commissariat and Transport Staff and the Army Service Corps was renamed the Commissariat and Transport Corps. At the time a new form of artistic expression known as the Art Nouveau movement was sweeping Victorian Britain and the principal motif of the Commissariat and Transport Staff was expressed in stylised, art nouveau lettering as a cypher in the centre of officers' helmet plate stars. Waist belt clasps were of typical 1855 pattern with the new title placed upon the circlet, and a standard British Army Crest of Lion and Crown in the centre. Perhaps as a foil for these relatively simple designs the gilt button was especially elegant, featuring a scalloped edge and horizontally ribbed dome, with the Army Crest embossed in the centre.

The Army Service Corps

1889 to 1902

In December 1888, the Commissariat and Transport Staff and Commissariat and Transport Corps. amalgamated with the War Department Fleet of Army administered transport vessels to form a new, far more utilitarian, second Army Service Corps, and for the first time officers and other ranks served in a single, unified organisation. There had historically been constant friction between the old control officers and the combatant officers; the former were said to be not officers at all but civilians. The Royal Warrant transformed the 'mere clerks' into combatants and the department was no longer despised. Divided into Supply and Transport Branches, the Army Service Corps provided bakers, butchers, slaughter house men, staff clerks, packers and loaders, tailors, shoemakers, wagon/cart drivers, farriers, saddlers, horse collar makers and wheelers. Instead of art nouveau, a more traditional cursive script was used for the new central cypher in the helmet plate star and pouch belt badge, but this was later replaced with a more avant garde style monogram that became familiar over the next 70-years. Officers waist belt clasps retained their basic design, but with the new corps title on the circlet, and the gilt button bore the Royal cypher within a Garter surmounted by a crown. The garter inscribed "ARMY SERVICE CORPS".

NEXT

THE ARMY VETERINARY DEPARTMENT,

ARMY PAY DEPARTMENT &

MISCELLANEOUS CORPS

The Army Medical Services

1881 to 1902

In 1855 the Medical Staff Corps of men below officer rank employed as medical orderlies was formed in response to the needs of the Crimean War. These medical orderlies were Officered by long-standing Regimental Surgeons who wore the uniforms and insignia of their own regiments, but with unique features to make clear that they were non-combatant, medical members of the regimental staff. In 1857 the Medical Staff Corps was re-designated the Army Hospital Corps, which had a few officers in specialist, but non-surgical roles. Regimental employment ceased in 1873 and surgeons became members of the Army Medical Staff within an Army Medical Department and thus had to forego regimental uniform and adopt unified dress and insignia of special identity for the first time. In 1884, The Army Hospital Corps and the Army Medical Staff were merged to form a single Medical Staff Corps, which in 1898 was renamed Royal Army Medical Corps, thus creating an organization of all specialties and all ranks.

The Army Ordnance Services

1881 to 1902

“The English Ordnance Department goes back into an older history than the Army. There were Master Generals of the Ordnance and Boards of Ordnance centuries before there were Secretaries of State for War, or Commanders in Chief.” The supply and repair of technical equipment, principally artillery and small arms, was the responsibility of the Master General of the Ordnance and the Board of Ordnance since the Middle Ages.

Much of the Ordnance structure was tied to London, with a mixture of largely civilian staff and a small number of military specialists, neither of which were ordinarily geared to deploy into the field. Instead, they carried out their peacetime function day-to-day, but were organised into an ad hoc, deployable 'Ordnance Field Train' as and when essential. Although far from agile, this arrangement muddled through thirty campaigns of varying magnitude until being found entirely wanting during the Crimean War that ended in 1855. Following a number of inquiries that castigated both the Commissariat (see previous section) and almost all of the Field Train system, the Board of Ordnance was abolished and, along with the Royal Artillery and Engineers, its functional responsibilities were passed to the War Office.

Following the Crimean War the Military Store Department (MSD) created in 1861 granted military commissions and provided officers to manage stores inventories. In parallel a subordinate corps of warrant officers and sergeants, the Military Staff Clerks Corps (MSC), was also created to carry out clerical duties. These very small corps, still based largely in London, were supplemented in 1865 by a Military Store Staff Corps (MSSC) to provide soldiers. In 1870 a further reorganisation, ostensibly to simplify management, resulted in the MSD, MSC and MSSC being grouped with the Army Service Corps (ASC) – previously covered in the Commissariat section of this series - under the Control Department. The officers remained a separate branch (Ordnance, or Military Stores) in the Control Department, but the soldiers were absorbed into the ASC. This arrangement lasted until 1876. The Control Department was disbanded in 1876. The Ordnance/Military Store officers joined a newly created Ordnance Stores Department (OSD). Five years later, following the Cardwell/Childers Reforms of 1881, the soldiers also left the ASC and became the Ordnance Store Corps (OSC). In 1894 there were further changes. The OSD was retitled the Army Ordnance Department (AOD) and absorbed the Inspectors of Machinery from the Royal Artillery (RA). In parallel the OSC was retitled the Army Ordnance Corps (AOC) and at the same time absorbed the Corps of Armourers (of sergeant to warrant officer rank) and the RA's Armament Artificers. Once again, this convoluted organisation continued to be characterised by a divide between officers and their men, and what follows are the insignia and principal uniform accoutrements of the officer elements of the Army's Ordnance Services from 1883 until the close of Victoria's reign in 1902.

The Army Veterinary Department

1881 to 1902

Prior to the 1790's there were no qualified veterinary surgeons (either military or civilian). Formal veterinary training began in 1791 with the foundation of a School of Veterinary Medicine in London. The Service was founded in 1796 'to improve the practice of Farriery in the Corps of Cavalry' when the public was outraged that more Army horse were lost as the result of poor care than by enemy action. The Head of the Veterinary School was appointed as Principal Veterinary Surgeon to the Cavalry, and Veterinary Surgeon to the Board of Ordnance (responsible for Artillery and Engineers). He was also charged with the formation of the Army Veterinary Service through which a qualified veterinary surgeon was appointed to each cavalry regiment. Veterinary surgeons were commissioned into the army, with appointments organized on a regimental basis and, as with the medical surgeons, regimental dress was worn. The Veterinary Medical Department was formed in 1858. In 1881 the regimental appointments were abolished (except for the Household Cavalry) and an Army Veterinary Department (officers) formed followed by an Army Veterinary Corps (other ranks) in 1903, and in 1906 it combined with the Army Veterinary Department to become a corps of all ranks, but without change of title.

The Army Pay Department

1881 to 1902

For centuries, the responsibility for organising the pay of British soldiers had fallen to individual regiments. Regimental colonels, for whom their regiment was virtually a personal estate, engaged clerks and agents to handle regimental pay and finance. Some were inevitably more efficient than others. In the field all transactions were conducted in coin. For the pay of soldiers it was issued from the Treasure Chest to the Captains of companies by the Treasurer-at-War on the basis of muster rolls. All dealings with soldiers were in the hands of the Captains and their clerks. These regimental pay duties were jealously retained by the Captains, each of whom was assisted by a numerate non-commissioned-officer told off to act as the company pay sergeant. During the Eighteenth Century some Colonels of Regiments gave the title "Paymaster" to officers who became involved in the payment of soldiers as a main part of their duties and this practice was formalised in 1797 when Paymasters with special commissions were gazetted to the Regiments, under the so-called “New Military Finance”. Eighty years later, following the administrative disasters of the Crimean war and encouraged by the reforming zeal of Edward Cardwell, it was decided to bring all Army Paymasters into a single organisation to be known as the "Army Pay Department" where officers with suitable financial and clerical skills were to be employed to ensure the regular payment upon agreed and universal pay rates.. The Royal Warrant giving effect to this was signed by Queen Victoria on 22nd October 1877 and the Department came into being on 1st April 1878. Four years later its complementary organisation comprised of non-commissioned officers was established and called the "Army Pay Corps".

Inspectors of Army Schools

1881 to 1902

The education of British soldiers and their children had been a feature of army life since the mid eighteenth century. Regimental schools were established in 1812 and focused primarily to educate young soldiers and the sons and had a long precedence in the British Army, and not only for soldiers, but as well as for the sons and daughters of soldiers. By 1840, the War Office had agreed to the appointment of a paid schoolmistress to each infantry battalion and cavalry regiment, and at each infantry depot. A Corps of Army Schoolmasters was established in 1845. It was made up of senior non-commissioned officers, but overseen by a small number inspectors. Initially, it only taught soldiers. But in 1859, it was also put in charge of the Army’s libraries and regimental schools. The regimental schools were replaced by garrison schools in 1887.

Toward the end of 1857, the nucleus of an inspectorate had been formed and was soon to comprise a pool of Army schoolmasters at home and regimental officers overseas. Collectively, all of these inspectors provided a network of inspection from Ireland to Calcutta, their reports providing a vivid picture of the state of Army education worldwide. Each inspector was to ensure that the timetable was strictly adhered to; that only approved books were used; that the schoolmaster and mistress were fit for their work and that accommodation was up to standard. At the close of each inspection, the inspector submitted his report to the Inspector-Genera1 of Army Schoo1s, and at the end of the year the latter consolidated his findings in an annual return to the Secretary of State. In 1870 it was recommended that the Inspector of Army Schools coordinate and supervise the work of his subordinates. The number of inspections to which the children's schools were subjected had multiplied to as many as four a year by 1870. Over the next few years this was reduced, but although the chi1dren's schools were only examined thoroughly once a year, they were still subjected to half-yearly visits whereupon a report was submitted to the Inspector of Army Schools based upon the general management of the schools and the quality of teaching. This pattern of a formal annual inspection, with an interim visit or less formal inspection, continued until the early twentieth century when the regulations were gradually relaxed. Inspectors of Army Schools had their own, discrete uniform and insignia that was instantly recognisable to pupil and soldier alike.

Governors of Military Prisons

1881 to 1902

Prior to 1845 soldiers convicted of offences under military, or civil law were either, transported to one of the Colonies, or incarcerated in civil gaols with some of the latter returning to service on completion of their sentence. However, placing soldiers under sentence in close confines to the nefarious influence of felons was unpopular, and from 1846 district military prisons were opened in Chatham, Gosport, Devonport, Weedon, Greenlaw, Dublin, Limerick, Cork, Athlone and, later Aldershot, as well as Colonial stations over succeeding years. These were all places where military warders, albeit with a civilian status were employed. Some of the warders were former regular soldiers and all were equipped and clothed in accordance with army clothing regulations. Military prisoners were treated harshly, with hard labour being a frequent task given to prisoners, and in the spring of 1895 a committee was formed under the chairmanship of Lord Monkswell to ‘consider the regulations affecting the discipline and diet of soldiers confined in military prisons and to report whether any changes were desirable’. One of the key members of the committee was Lieutenant Colonel Michael Clare Garsia, who had been acting as the Inspector-General of Military Prisons since 1898. Garsia was concerned about the military prison system. The skills and ability of the guards was very variable, with very few possessing much in the way of compassion and he realised that improvements in the system could only be achieved by recruiting staff who were ‘possessed of the military spirit and thoroughly efficient as instructors’. Therefore, he devised a set of qualities and qualifications required for a new corps of military prison staff, who he saw should be experienced non-commissioned officers. On the 26 November 1901, the Military Prison Staff Corps was formed within the British Army with the purpose of running the Army’s prisons and detention establishments in accordance with the principles set down by the committee. Governors of military prisons had always been selected from experienced officers on half-pay, or those who were unfit for more active employment, and were dressed in a special uniform and insignia specific to their role.

Provost Marshalls & Military Police

1881 to 1902

The title of Provost Marshal is one the most ancient appointments in the service of the British Crown, with its origins lost in antiquity. One of his most important duties was to maintain the ‘King’s Peace’ with the feudal armies, and so he was personally appointed by the King. Although primarily a military officer, the Provost Marshal was also responsible for maintaining the peace “12 miles about the Prince’s person”, and dealt summarily with all offenders, military and civilian alike. In his military capacity the Provost Marshal had assumed most of the duties as we would recognise them today by the beginning of the fourteenth century, and was on the customary establishments of all field forces from then onwards. In the Civil Wars, both sides appointed Provost Marshals and the Provost Service became part of the establishment of the Standing Army at its inception in 1660, but was only called into being with the Army on active service. However, in 1685, the appointment of Provost Marshal General became a permanent post and Provost Marshals were appointed to various Formations, Garrisons and to individual Regiments. The Duke of Wellington took a great interest in his Provost Service, issuing comprehensive orders laying down Provost duties and those of his Provost Marshals and their assistants. (His “Bloody Provosts”). Following the outbreak of the Crimean War (1853-56), a Mounted Staff Corps (MSC) was formed to assist the Provost Marshal with the majority of recruits coming from the Irish Constabulary and some from the Metropolitan Police. The MSC was disbanded at War’s end.

The modern history of the Military Police commenced with a War Office circular dated 13th June 1855, when certain cavalry regiments were directed to supply Non-Commissioned Officers and me of “five or ten years’ service, sober habits, intelligent, active and capable of exercising a sound discretion” to form a permanent Corps of Mounted Police at the new Cantonment that had been established in Aldershot in 1853. On the 4th July 1855, a total of twenty-one other ranks was authorised, in order: ‘To be employed as a Corps of Mounted Police for the preservation of Good Order in the camp at Aldershot, and for the protection of the inhabitants of the neighbourhood’. In 1865, the strength of the Corps increased to 32 mounted men. In 1872, a detachment of Mounted Police attended the Army’s annual manoeuvres under an Assistant Provost Marshal appointed for the occasion, and two-years later the first set of printed orders were published for their guidance.

After authorisation in July 1877, the Military Mounted Police (MMP) was established as a distinct Corps for service at home and abroad just 4-weeks later in August and given an increased establishment of 75: 1 sergeant-Major; 7 sergeants; 13 corporals; 54 privates; and 71 horses. Military Police were serving in Woolwich, Shorncliffe and Portsmouth in addition to Aldershot. On the 1st August 1882, a sister Corps to the MMP was formed for special service in Egypt – the Military Foot Police (MFP). The Foot Police were recruited entirely from men recalled to the Colours, who had served with the Metropolitan Police Force. The MFP were authorised as a permanent Corps in July 1885, with an establishment of: 1 sergeant-major; 13 sergeants; 17 corporals; and 59 privates. The end of the century saw the Military Police with a strength of just over 300, with detachments at all the garrison towns in United Kingdom, and permanent detachments in Cairo and Malta.

The Royal Military Academy, Woolwich

The Royal Military Academy (RMA) was opened by authority of a Royal Warrant in 1741: it was intended, in the words of its first charter, to produce "good officers of Artillery and perfect Engineers". Its 'gentlemen cadets', who initially ranged in age from 10 to 30; were accommodated in lodgings in the town of Woolwich to begin with, but this arrangement was deemed unsatisfactory due to their unruliness, so in 1751 a Cadets' Barracks was built just within the south boundary wall of Woolwich Warren, and the cadets had to adjust to a more strict military discipline. Education in the Academy focused at first on mathematics and the scientific principles of gunnery and fortification. In the 1760s the Military Academy was split: younger cadets entered the Lower Academy, where they were taught reading, writing, arithmetic, Latin, French and drawing. If they performed well in examinations they were allowed to proceed to the Upper Academy, where they learned military skills and sciences.

The possibility of moving the Royal Military Academy out of the Warren was mooted as early as 1783. Eventually a new complex of buildings was built on a site at the southern edge of Woolwich Common between 1796 and 1805 and opened for use the following year. 128 cadets moved to the new Academy: these comprised the four senior years. Of the younger cadets, sixty were kept at the Warren and another sixty were sent to a new college for junior cadets at Great Marlow. In 1810, military cadets of the East India Company, who had previously been educated at the Academy, were moved to a new college at Addiscombe. During the years that followed the status of the Woolwich cadets changed: rather than being considered junior military personnel, as had previously been the case, they were removed from the muster roll and their parents began to be charged fees for attendance. In this way the Academy took on something of the ethos of an English public school. Following the demise of the Board of Ordnance in the wake of the Crimean War the Academy was inspected by a commission which recommended changes: the minimum age for cadets was raised to fifteen and more specialist training was added. As part of these reforms the Academy complex was enlarged in the 1860s, with a view to accommodating all cadets on the same site and the frontage was extended with the addition of new pavilions at either end. These contained new classrooms and accommodation provided in blocks behind.

As had always been the case, in 1880 the cadet's dress was a simplified version of that worn by the Royal Artillery, regardless of the cadets regimental destination. As such it comprised blue tunics and frocks with red facings, together with the pill box cap in undress, and for full dress the blue, universal helmet that had replaced in 1878 the fur busby that had been worn since 1870. The colours blue and red had long been associated with the Board of Ordnance to which all of the cadet's intended corps belonged. No collar badges were worn, but there were special buttons, and waist belt and helmet plates with the designation 'Cadet Company' added to the standard RA design.

The Royal Military College, Sandhurst

Until 1870, the usual way for an officer of the cavalry or infantry to obtain his commission was by purchase. A new candidate had to produce evidence of having had "the education of a gentleman", to obtain the approval of his regimental colonel, and to produce a substantial sum which was both proof of his standing in society and a bond for good behaviour. When a promotion vacancy occurred, the senior officer of the immediate lower rank in the same regiment had the first claim to be promoted, subject to being able to produce the as appropriate sum laid down by Parliament for the rank in question. Promotion to colonel and above was by seniority without purchase. Staff appointments, which carried promotion, were by selection, not purchase, but an officer reverted to his regimental (normally purchased) rank on expiry of tenure. When an officer left the Army, the price of his last commission was refunded, thus realising a large capital sum for investment elsewhere. The system was subject to abuse, as very rich men could pay their juniors not to take up their right to promotion, but had the advantage of allowing wealthy officers to obtain command of a regiment in their twenties, while at the peak of their fitness and energy. By contrast, in the Board of Ordnance corps, where promotion was by seniority, it was common to find officers in their forties still serving as subalterns.

The Junior Department of the Royal Military College (RMC), formed as a college of gentlemen cadets, began in 1802 at Remnatz, a converted country house at Great Marlow. When the experiment proved successful, a new site was purchased at Sandhurst Park, Berkshire, where the new RMC was first occupied in 1812. The purchase system was still in force, but gentlemen cadets who completed the course and were recommended by the College authorities were granted their first commissions without purchase. Moreover, when there were more candidates than vacancies, RMC cadets were given priority. Despite these advantages, the RMC gained a reputation for disorderly behaviour comparable with unreformed public schools of the period, with the average age of the cadets being about fifteen, although the age was gradually raised until the College was closed in 1870. In that year the purchase system was abolished and first commissions were, for a time, awarded by written competitive examination. The buildings were used to train successful candidates in military skills while they waited to join their regiments, but this did not prove satisfactory, and in 1877 the examination became for appointment to the RMC as a cadet, rather than for a commission. In practice the cost of the college fees was much the same as that formerly charged for an ensign's commission, and this, plus the school fees required in preparation for the entry examinations, meant that the social composition of the Army's officers remained unchanged. The RMC was not large enough to train all the subalterns needed by the Army, so an alternative route, favoured by those who failed entry to the College, was to obtain a commission by nomination in the Militia. It was then possible to transfer to the Regular Army after a period of full-time service and passing the College's final examination.

In 1880 the dress of RMC cadets was based upon that of line infantry and comprised scarlet tunics with the dark blue facing's associated with Royal approbation. Glengarry caps were adopted as undress head wear in 1874, and for full dress the blue, universal helmet was worn, having replaced the long standing shako in 1878. There were no collar badges, but there was a special RMC badge for both types of headdress, as well as buttons and waist belt clasps.

The Unattached List

The term "Unattached List" was one that was long used by the British Army and associated Colonial and Dominion forces to describe the status of regular and auxiliary personnel who are not assigned to a permanent regimental, or staff establishment, but who are trained and hold a military rank. In the case of commissioned officers this was generally either at the beginning of their career, before assignment to a parent regiment, or at the latter part of their career, when a suitable active appointment cannot be found for them. In the latter case such officers were often elderly and debilitated in some way, but still capable of holding sedentary appointments where their long experience was of use. The list was a means of keeping track of numbers and public expenditure as it pertained to officers in that category. Elderly officers employed in relatively inactive roles would generally wear the uniform of their late regiment, or rank, together with generic buttons and waist belt clasps making clear their unattached status. From 1861 there was also a separate, Unattached List (India) that described supernumerary European SNCOs, WOs and 'honorary officers' (commissioned rankers) from the British Army serving with specialist corps of the Indian Army.

The Garrison Staff

Although historically lauded, the combined Cardwell and Childers Reforms that reached their conclusion in 1881, did little more than continue the process of sweeping away the pre-Crimean War army, and inadequate War Office organisation. However, the two men undoubtedly blazed a trail for continued reform under able legislators like Lord Stanhope, who for the first time clearly articulated set purposes for the British Army and embodied them in what became known as the Stanhope Memorandum of 8th December 1888. Of the five purposes laid out in the memorandum, three were connected to military infrastructure at home and abroad. Namely; supporting the civil power, garrisoning fortresses (and coaling stations), and mobilising two Army Corps of regular troops rapidly for home defence, plus a third made up partly of regulars augmented by the militia. All of these tasks required the staffing of large garrisons such as Aldershot, Colchester, Woolwich, and the Curragh, as well as defended ports and numerous smaller stations, with officers and men to ensure that systems continued to function even when units deployed and took their regimental officers with them. These administrative officers were often from the Unattached List, or re-employed, retired individuals from the Reserve of Officers, and categorised as Garrison Staff. The garrison staff specialised in 'Works, Buildings and Land', and carried out the administrative duties necessary to ensure that barracks infrastructure and services were in good order regardless of the number of soldiers in station at any one time. Not part of any specific unit, they wore generic uniform, but with insignia signifying their garrison role.

The Indian Staff Corps

Following the Indian Mutiny of 1857 perceived shortcomings in the way that British officers were appointed for Indian regiments led to a separate Indian Staff Corps being formed in 1861 and divided into separate lists for the Bengal, Madras and Bombay Presidency Armies. The lists were meant to provide officers for the native regiments and for the staff and army departments. RMC and RMA trained officers, destined for Indian regiments and corps, were generally placed upon the Unattached List of the British Army and then posted for one year to an India based Regular British unit in order to gain practical experience of military routine before being exposed to command of native troops. After that initial year they were transferred to the particular Indian Staff Corps list of whichever Presidency their intended Indian regiment was established within, and then posted to join their native unit. These officers wore the blue faced scarlet tunic and associated insignia laid down for the Indian Staff Corps in Dress Regulations of 1883, until such time as they had proven themselves efficient, passed an indigenous language qualification, and were taken onto the establishment of their native regiment.

NEXT:

SABRETACHES