Special Scottish Insignia From 1881 to 1902

By 1883 the uniforms and insignia of the Scottish Regiments in the British Army had evolved to become uniquely and distinctly different to all others. However, things had not always been that way and the outcome had been reached via a number of influences.

Even before the Parliamentary Acts unifying Scotland with England in 1707, Scotsmen had provided soldiers for regiments on the English establishment, albeit initially in some cases serving with, and paid for by, nations such as France and Sweden and thus strictly speaking mercenaries. The four most senior Scots regiments; the Royal Scots, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, the King's Own Scottish Borderers, and the Cameronian's were thus at first all a part of the English establishment and had initially worn the same uniform as the other line regiments, albeit with features such as a few pipers, and insignia with a recognizably Scottish aspect such as the thistle, to mark their origins. Nevertheless, for all intents and purposes these regiments, all of which were associated with the lowlands of Scotland, looked little different to any other regiment of the Army when the two, Acts of Union first created Great Britain.

The creation of Great Britain had not come without controversy and whilst the lower regions of Scotland were relatively settled, the more barren highlands had little order and soon required garrisons to ensure adherence to direction from London. As well as regular units of the standing army, it was eventually found convenient to make use of local manpower and, in 1725, six companies of highlanders were raised and dispersed in small detachments to act as a Watch and ensure the rule of law. The uniform was described by a contemporary figure as “a scarlet jacket and waistcoat, with buff facings and white lace, tartan plaid of twelve yards plaited round the middle of the body, the upper part being fixed on the left shoulder, ready to be thrown loose and wrapped over both shoulders and fire-lock in rainy weather. At night, the plaid served the purpose of a blanket, and was a sufficient covering for the Highlander.” This mixture of a British red coat with traditional highland dress began a style of dress that was to become synonymous with at first the highland soldier, and later the Scottish soldier as a whole. The dark colour of the tartan and the original role of the Regiment to “watch” the Highlands led to the regiment's title as the Black Watch. Further regiments associated with places, or family names such as Cameron, Seaforth, Argyll and Sutherland, as well as a Light Infantry regiment, were gradually added to the Army's standing establishment over the succeeding centuries.

The highland soldier was found to take readily to military service and even during the clan rebellions of 1715 and 1745 some highlanders remained loyal to the crown, and quite a number formed regiments to fight for the crown in both Europe and the Americas. By the time of the American War of Independence even the dissenting highlanders had largely made their peace and provided numerous, but often short lived regiments, to support the King and those loyalist elements that existed. The appearance of highland dress on the world stage led to it becoming iconic and began a romantic mystique that reached its height under the influence of Sir Walter Scott, who propagated a legend of colourful plaids and national headdress that greatly affected the dress of the growing numbers of highland regiments. In the period leading up to 1881, and the Cardwell/Childers Reforms, these regiments adopted a wide variety of idiosyncratic dress whose minutiae was the despair of the financiers responsible for funding it, and the variations of kilt, or trews, shoulder plaid, baldric, hose, bonnets and side arms became indelibly embedded in regimental identity. To these items were added unique insignia, such as sporran cantles, plaid brooches, shoulder belt, dirk belt, and bonnet badges, that in most cases were significantly different to the insignia worn by the lowland Scots and various English, Welsh and Irish line regiments. Not even the Foot Guards of the Royal Household had such a wide panoply of dress and insignia.

Unlike the lowland Scots the highland regiments had just one battalion and, as the 1881 reforms required the regiments to pair up, this led to some uneasy mergers, as well as the reunification of old friends. As part of this reorganization some highland regiments that had worn trews merged with regiments that had worn kilts, and regiments with diced (chequered) headdress merged in some cases with regiments that had plain headdress. The biggest change of all was imposed on the lowland regiments, who for the first time were to wear the recognizably Scottish dress hitherto associated with the significantly more junior highlanders. As well as doublets, dirk belts and shoulder belts for broadswords, each with newly arranged iconography, they were to wear tartan nether garments, although kilts were a step too far and trews were agreed as a marked differential, albeit that the long standing existence of their regimental piper's kilts and insignia had played a part in design. Undoubtedly, agreeing the merger of dress and insignia was a significant challenge, but by 1883 and the promulgation of the first Dress Regulations for the new regiments, a reasonable compromise had been reached. What follows then is a depiction of those aspects of dress that are special to the Scottish regiments alone, and so confined to the officers' shoulder belt plates, dirk belt plates and plaid brooches that emerged from the deliberations forming the new regiments.

Shoulder Belt Plates

The adoption by infantry officers of a shoulder belt to carry their swords, rather than the previous practice utilizing a waist belt seems to have come about either, just before, or during the American Revolution. No special order to do this has ever been traced, and it seems to have originated as an expediently quick way to sling the belt over the shoulder, rather than round the waist under the coat and waistcoat. As so often with these things an adaptation of dress brought about by field conditions. Initially the belt was worn with its original waist-belt clasp, but this was gradually replaced by a purpose designed plate worn first as a clasp, or buckle, but which inevitably became an adornment. Initially only a few regiments had distinctive regimental badges, and the vast majority had only their regimental number allocated in 1751, together with a wreath, or spray of leaves, often surmounted by a crown. From 1782 the allotted County titles of that year were often added, and over time the shape of the plate varied between oval, elliptical, and oblong and gradually increased in size, featuring fine workmanship and increasingly elaborate designs incorporating battle honours, and regimental emblems as they evolved. Highland Scots regiments had long worn the equivalent, 'baldric' shoulder belt to carry their broadswords and over time these were modified to combine with British Army uniform and display a similar plate with honours and unit icons. In 1838 officers of field rank (1) were ordered to wear the waist belt again with their sword suspended on two straps, but company officers continued to wear the shoulder belt and plate until 1855, when all but the Highland regiments adopted a waist belt clasp and slings. This situation continued until 1881, when the Cardwell/Childers Reforms decreed that the Lowland regiments of Scotland, who had hitherto worn the same dress as English, Welsh and Irish regiments, would adopt a more recognizably Scottish dress with Broadswords and Dirks (2) . Even so it took over a decade for all these changes to take place, and some of the more reluctant regiments, such as the Royal Scots, did not readopt the shoulder belt plate until 1902. What follows are plates that display the shoulder belt plates worn by the Scottish regiments, both Highland and Lowland, of the late Victorian era and its transition over to the reign of King Edward VII.

(1) Majors, Lieutenant Colonels and Colonels.

(2) The unique Scottish dagger worn on a separate waist-belt

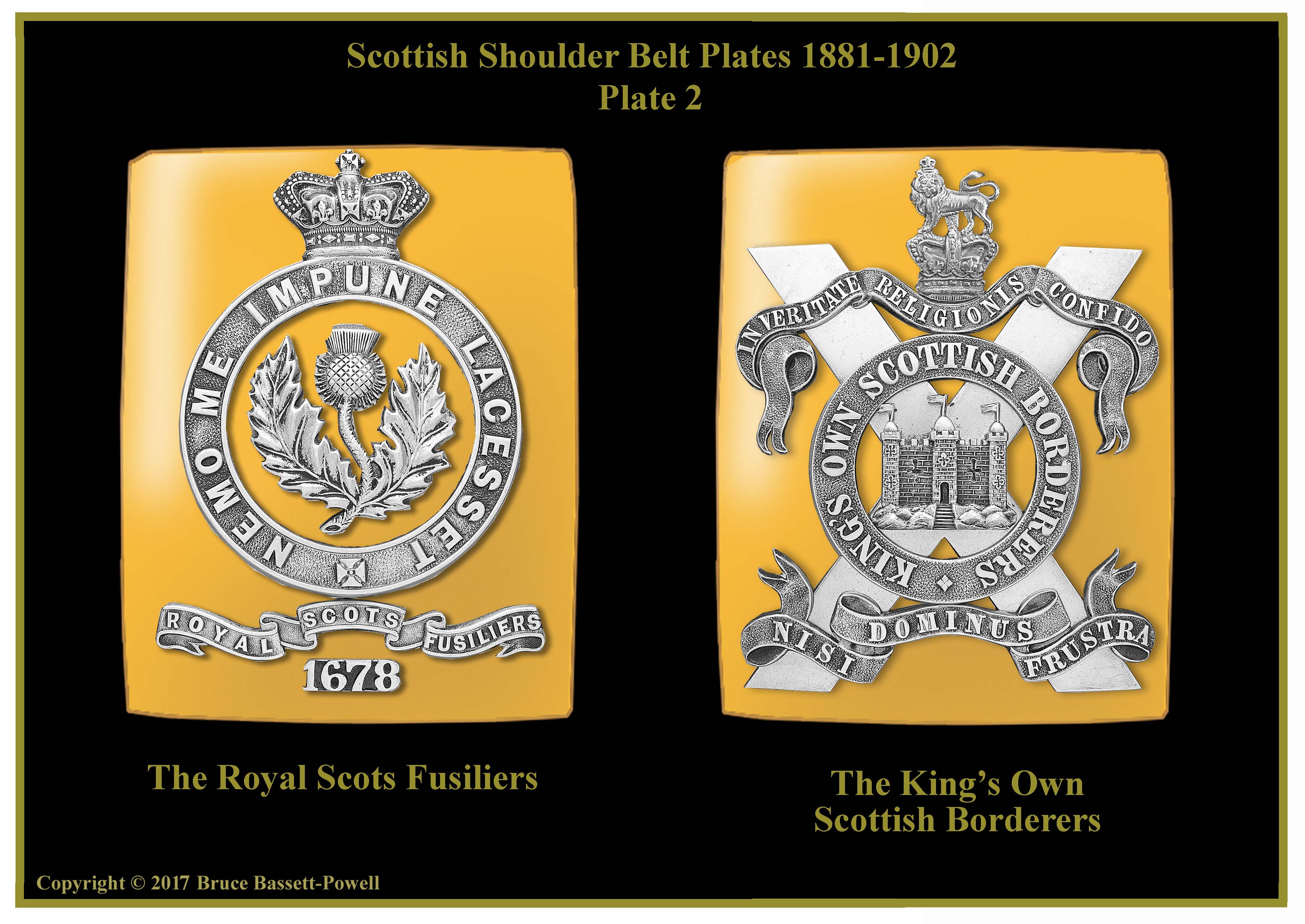

Although the shoulder belts and plates worn by the highland regiments had been established by 1883, The lowland regiments were not as quick to change. The pattern for the Royal Scots Fusiliers was sealed in 1896 and appeared in the 1900 Dress Regulations. The Royal Scots and King’s Own Scottish Borderers were both sealed in 1902 and appeared in the regulations of 1904.

The Brooches for the Full, or Shoulder Plaid

By the 19th Century the one piece, twelve yards long tartan plaid mentioned in the introduction to this appendix had in the British Army evolved to become two separate parts; the kilt and the full, or shoulder plaid. It became the norm for soldiers to wear just the kilt and only the officers, pipers and highland bandsmen to have in addition the full shoulder plaid. The latter matched the sett of the kilt, was usually almost twice the height of the wearer, and pleated the whole length, but with half sewn shut so that the pleats cannot open. In wear it is swathed around the wearer's chest, under the right arm and pulled in close to the body. It is then twisted on the left shoulder with one free end falling behind the wearer's back and tucked into the dirk belt, and the leading edge of the other free end is pulled forward and let fall over the wearer's left shoulder. The forward edge and face of the plaid is secured by a brooch on the right shoulder. These brooches were initially quite plain and functional, but as with the shoulder belt plate it eventually became an ornament on which to display regimental iconography and battle honours. The finest examples of brooch were worn by officers and lesser types by pipers and some of the more senior enlisted ranks. By 1883 the officers' brooches of the old numbered Highland regiments had had elements of their design combined with those of their partner units and new arrangements were agreed to ensure inclusion of all the principal features. In addition to the shoulder belt plaid there was also the fly plaid, or scarf, which was smaller and worn in a simpler way suspended from the shoulder by some sergeants. It too was secured by a regimental brooch, but of plainer design. The Lowland regiments never did adopt the shoulder plaid, except for pipers and in some cases, bandsmen.

This section of the Special Scottish insignia will show these beautiful objects as they appeared at their adoption between 1883 and 1902.

Sporran Cantles for Officers of Highland Regiments

1881 to 1902

The additional highland regiments that were formed subsequently to the Black Watch and who adopted the same style of dress, led to ever greater wear of the kilt as a nether garment within the Army. The absence of pockets in this type of clothing meant that the highland soldier had to find something in which to carry the items that other soldiers could place in medieval style belt pouches or, as uniforms evolved, the pockets of their breeches. The items carried ranged from rations in the form of oats, to money and other personal items needed readily to hand. It became convenient to adopt a low slung purse, or in Gaelic, Sporran, which was suspended on a strap below the invariably large dirk belt buckle, where it was in easy reach. Initially the sporran took a rudimentary, purely functional form in plain leather and was worn on a day-to-day basis, but as with the other items of highland regimental dress, over time more decorative fur pelts were used with the hair retained and tasseled cord decoration and insignia added, so that the highland soldier's sporran took on a more distinctive and unique form. For officers this development was mirrored to an even greater degree of decoration and two styles evolved, a general pattern for Review Order (1) and a more elaborate version for Levee Order (2) that was more intricately decorated, invariably with the same gilt or silver metal tops to the sporrans, but with ornate gold cords and tassels arranged beneath. The metal top piece was known as a Cantle and, as with other metal items of regalia, it became an object on which battle honours and regimental icons could be placed. This section of the Special Scottish Insignia Appendix displays the regimental Cantles that were fitted to the sporrans (3) between 1883 and 1902, so that their intricacy and craftsmanship can be appreciated. As with so much of the highland soldier's dress the Sporran, which had started out as a purely functional item became an item of ceremonial grandeur that is today seen as an essential item of Scottish National dress.

1) Review Order was worn at events where officers and their soldiers paraded in formed bodies for formal review (inspection) by a senior officer.

2) Levees were events where officers were individually presented to their Sovereign, or very senior members of the Royal Family. Such occasions required the wearing of more decorative and expensive items of dress that each officer was required to purchase as part of his personal kit.

3) Most highland regiments used the same cantle on both types of sporran, but the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders used a cantle only on their levee pattern. For Review Order the regiment wore a badger's head on their sporran.

THE DEPARTMENTAL

AND OTHER CORPS

Miscellaneous Items of Special Scottish Insignia

The adoption of what had hitherto been exclusively Highland items of Scottish military dress had not always gone smoothly. There had initially been some reluctance, especially by the Royal Scots, who had their own strong tradition born of long existence, and had for many years been belligerents of the Highlanders. There were also some in Royal Scots Fusiliers circles who felt the same way, partly for similar reasons, but also because changing their dress placed them at odds with the other fusilier regiments in terms of their immediate appearance, whereas there had previously been a great degree of uniformity. The King's Own Scottish Borderers had long association with Scotland's capital city, Edinburgh, and so were more immersed in the new fad for highland dress, but they too had similar cause to have some concerns. Nevertheless, over the immediate decades after the 1881 reforms, the changes in dress decreed by the 1883 Dress Regulations took place, and this section of the Special Scottish Insignia Appendix looks at the sequence of events.

In 1877 the 21st (Royal North British Fusilier) Regiment of Foot had their title changed to become the 21st (Royal Scots Fusiliers) Regiment of Foot and the 1855 pattern waist belt clasp, which had hitherto borne the earlier title, was changed to reflect the new designation and is shown here. From 1883, however, the regiment promptly adopted the Highland style Dirk Belt Plate that is shown on the relevant plate in the main part of the series. The Royal Scots and the King's Own Scottish Borderers followed suit with their own Dirk Belt Plates in 1896, and all three regiments ensured that the iconography on the plates reflected their unique identities.

Headdress too, began to take on a distinct Scottish slant, but the adoption of a Highland feather bonnet would have been a step too far for the Lowlanders and, whilst efforts turned to seeking an alternative to the 1878 universal helmet, the strong intent was to find something strikingly different to both, the Highlanders and the other line regiments of the Army. The Cameronian's (Scottish Rifles) found inspiration in the Highland Light Infantry, with whom they shared both light infantry forebears and a depot, and in 1890 they adopted a similar shako to that regiment, but in rifle green, together with the badge comprising a Mullet, representing the old 26th, and a Horn, representing the old 90th . The Royal Scots and the King's Own Scottish Borderers took a while longer to find a solution that suited them, but over the period 1902-1903 they both adopted a stiffened and set-up, or in Scottish terms 'Cocked' Kilmarnock Bonnet, which had the presence and distinction that reflected their long histories, and on which they elected to wear the same badge as used on their glengarry caps. The old town of Kilmarnock had long made woollen bonnets for the British Army, and so there was some satisfaction in Scotland that this choice of headgear was a pleasingly apt solution. The Black Watch, too, had chosen an idiosyncratic feature for their full dress headdress, which departed from what was laid down in the 1883 regulations. Instead of the badge shown on the main series plate, they from the outset adopted the Sphinx badge that had been so prized by the old 42nd and which according to tradition commemorated their capturing the Colour of Napoleon's so-called “Invincible” Legion at the Battle of Alexandria, in 1801.